Teresa Brzóskiewcz (1929-2020). A retrospective

Teresa Brzóskiewicz at one of her sculptures, Academy of Fine Arts Warsaw, ca. 1952

For more than half a century, efforts have been made to reformulate history to make space for creative women. Among them are many female artists who were overlooked by art history despite their success during their lifetimes. Encountering their work often raises the question of why they were forgotten; after all, they were incredibly talented, accomplished a great deal, and left behind exciting works. Yet, the opposite occurred.

A striking example is the sculptor Teresa Brzóskiewicz, whose name does not appear in studies of the history of Polish sculpture in the second half of the 20th century. This is surprising, given that five of her works—excluding the tombstones in Powązki Cemetery—remain publicly accessible in Warsaw.

The process of restoring the memory of female artists, whose most creative years fell during the communist era, has already begun. This revision of our history is producing fascinating results, uncovering several outstanding achievements. These women were once well-known, their works appreciated by both the public and art critics. However, historical events, coupled with their personal lives, caused them to disappear from the art scene.

Starting in 1989, the years of political transition were particularly unfavorable for these female artists. Polish culture of the 1990s was destructive, intolerant, and erased everything that did not conform to the new vision of modernity. Generational issues, political animosities, and the desire to "catch up" with the West were intertwined, showing how remembering is a political issue. We must reverse the mechanisms of power and restore the memory of these artists. Today, we view the art of the communist period from a different perspective, seeking what is important and valuable.

In the second half of the twentieth century in Poland, where emancipation proceeded with a different rhythm than in the West, many sculptors were active; their work was not restricted by law or moral pressure, although there were always culturally grounded limitations. A visible sign of full equality in this regard was the exhibition Sculpture in the Garden organized in 1957 at the Warsaw headquarters of the Association of Architects of the Republic of Poland, featuring four female and four male artists. This event resonated within the sculptor community and must have been seen by Teresa Brzóskiewicz, who that year graduated as an aspirant from the Faculty of Sculpture at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts.

Teresa Brzóskiewicz (right) with colleagues at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, ca. 1952

Born in 1929, she belonged to a generation peculiarly marked by cataclysms and successive breakthroughs in the history of the 20th century: a childhood in the shadow of war, studies during the Stalinist period, and a difficult start during the reign of the Socialist Realist doctrine. The rise to power of a new team within the communist apparatus in the mid-1950s brought changes in international relations, which benefited artists. Many went abroad for scholarships, especially to France; Teresa Brzóskiewicz was among them, receiving a scholarship from the Ministry of Culture and Art. In Paris, she initially continued her studies by attending classes at l'Académie de la Grande Chaumière, which allowed her to enter the Parisian art community. She also attended lectures at the Ecole du Louvre. Out of economic necessity, but also driven by her childhood and youth fascination with theater, she decided to try her hand at puppetry. Along with a group of friends, she organized a puppet theatre, for which she made most of the puppets. The income from these performances supplemented her modest stipend.

She then worked as a casting technician for a wealthy French amateur sculptor. The financial independence she gained from this allowed her to rent her own studio, where she could create without the constraints of "the mundane of life." Sculpture began to come to the fore in her search for new forms of expression.

In general terms, it can be said that in France, the tradition of figural sculpture was still dominant; in Britain, Spain, and the USA, abstract tendencies were popular. In both environments, expression and innovative approaches to sculptural materials were essential. We do not know the artistic proclivities of Teresa Brzóskiewicz from this period, but she undoubtedly came under the influence of the French school with its emphasis on the human figure; at the same time, she opposed all literature based on construction. She mentioned this in an interview on the occasion of a solo exhibition in the fall of 1961 at Galerie Notre Dame in Paris.

Woman (ca. 1960)

The sculptures shown at this exhibition confirmed the artist's professed beliefs. These included Motherhood, Madonna, Nude, and the most abstract among them - Icarus. Unfortunately, there are only a small number of photographs from the exhibition published in the Parisian press, which show a female figure, most likely made of concrete, following the tradition of representations of a semi-reclined figure. Such a style would recur in the artist's later work, though in a different stylistic approach and with other materials. Similarly, The Woman from the Island of St. Marguerite, also shown in Paris, would find echoes in sculptures made in the 1960s and 1970s.

Additionally, from the Paris period comes the portrait of Cacau, a model posing for sculptors who could afford to hire him. Thanks to her acquaintances among French artists, Teresa Brzóskiewicz was able to attend sessions for free when Cacau posed. Later, she made portrait sculptures that were always remarkably expressive. Even before the Paris exhibition, the artist had a solo exhibition in Cannes and participated in the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. Several informative and flattering notes (reviews?) about the exhibition at Galerie Notre Dame appeared in the French press, along with a brief interview conducted with the artist by François Pluchart, a then-budding and later well-known critic.

She also successfully designs exhibitions, such as the artistic setting of the Polish pavilion at the International Students' Festival at the Cité Universitaire in Paris. She was awarded second prize for her design in 1960 and first prize in 1961, as well as the Silver Badge of the Polish Students' Association.

The positive reviews by French critics did not anchor Brzóskiewicz in Paris. In 1961, she returned to Poland. Besides personal reasons, this decision may have been influenced by memories of Poland's artistic life, which was undergoing a revival after years of political paralysis.

Immediately after her return, she had an exhibition at the Association of Polish Architects (SARP), and a year later at the MDM gallery, Warsaw's most important venue after Zachęta. Both exhibitions featured sculptures brought back from Paris, alongside new works. She continued her art, and three years later, she had another solo exhibition, this time in Sopot. Her artistic path began in this city; it was there, in 1947, that she started her studies at the State Higher School of Fine Arts before moving to Warsaw, where she received her diploma in the studio of Franciszek Strynkiewicz in 1953. Her professors in Sopot were Marian Wnuk and Stanislaw Horno-Poplawski, and in Warsaw, Tadeusz Breyer and Franciszek Strynkiewicz. In 1965, she participated in the Warsaw in Art exhibition, receiving an award from the Board of the Warsaw Branch of ZPAP. Working with various materials (stone, artificial stone, cast iron, ceramics, wood, and alabaster), Brzóskiewicz demonstrated her versatile education and creative abilities.

An essential stage in Teresa Brzóskiewicz's work was her stay in Denmark. In 1966, she received a grant from the Ministry of Culture and the Arts to attend Herning Højskole, a folk university in Jutland, where open-air sculpture workshops were organized with a local metal factory. During her stay, she created several large metal sculptures, including one 6 meters high, using welding techniques—the same techniques she later used for Warszawianka and Banners, among others. She also had a solo exhibition in 1966 in nearby Ikast. Several smaller forms completed at that time remain in private collections in Denmark. Unfortunately, the largest ones in the Sculpture Park in Herning were most likely destroyed after the People's University closed in the early 21st century. However, this Danish episode, in which Brzóskiewicz realized large-scale outdoor works for the first time in her career, had significant consequences for her further activities.

The 1960s were a dynamic period in Polish sculpture. On the one hand, official monuments were created, and the authorities announced competitions for their realization; on the other hand, artists experimented, looking for new materials, forms of expression, and ways to present sculptures in public spaces. One manifestation of this dynamic period was the organization of the 1st Biennial of Sculpture in Metal in Warsaw in 1968. Along Kasprzaka Street, dozens of metal sculptures were set up on the green belt separating the roadways to prove the unity of the worlds of art and industry, as well as the cooperation between artists and workers. The most creative sculptors of the time, mainly from the Warsaw milieu, participated, including Jan Berdyszak, Bronislaw Chromy, Jerzy and Krystian Jarnuszkiewicz, Tadeusz Sieklucki, and Adam Smolana. Teresa Brzóskiewicz contributed two works: Butterfly and Dawn. The latter survives and stands, along with other works from the Biennale, in the Wola square designated for their presentation after the reconstruction of Kasprzaka Street. This tall structure is made of metal elements, opening upward like a flower, topped by two smooth disks painted yellow. The now lost Butterfly was more expressive and organic at the same time due to its rough metal surface.

This lost sculpture is reminiscent of the works of Swiss artist Robert Müller, active and famous in Paris during the same period as Brzóskiewicz, who also created metal sculptures with forms and titles referencing the plant and animal world.

In addition to large outdoor works, Brzóskiewicz began creating expressive works combining metal and colored glass after her return to Poland from Paris. One such work, The Chopin Competition, was donated to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje as part of a collection given by Polish artists to the earthquake-ravaged city. Brzóskiewicz also used a combination of glass and metal elements in interior design.

The museum was built according to a design by three Polish architects: Waclaw Kłyszewski, Jerzy Mokrzynski and Eugeniusz Wierzbicki, commonly known as the Tigers, who won an international competition. Teresa Brzóskiewicz collaborated with them on several occasions, including the construction of the Mariner's House in Szczecin in 1972. She used a combination of glass and metal elements in the interior decoration and designed ceramic decoration on the facade. Unfortunately, the building no longer exists.

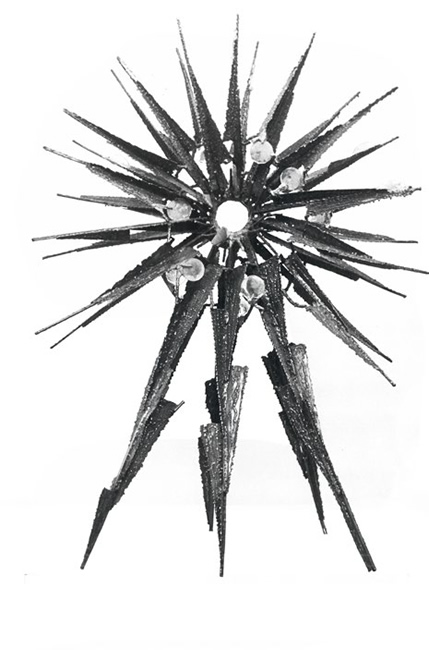

An expressive form was part of a project carried out as part of the utopian intention proposed by Marian Bogusz and Jerzy Olkiewicz to connect the National Museum in Warsaw with the Zegrzynski Reservoir through an artistically designed road. Teresa Brzóskiewicz collaborated with Janusz Laudanski and Tadeusz Wencel on this urban-architectural-sculptural project. The National Museum in Warsaw preserves a model of the sculpture showing an abstract form with a radially opening structure made of narrow pieces of polished metal that catch the light.

The initiatives characteristic of the 1960s, which began to forge cooperation between artists and heavy industry—such as the Biennale in Elblag, the Seminar in Puławy, and the exhibition in Wola—were continued by the Warsaw branch of the Union of Polish Artists (ZPAP), which organized an open-air workshop at the Warsaw Steelworks in 1977. However, it no longer produced the spectacular results of earlier events. Teresa Brzóskiewicz's sculpture, Warszawianka, created for the occasion and still standing in front of the building that once belonged to the steel mill, marked a return to a focus on the human figure. Made in metal, the elongated female figure echoes the earlier Woman from the Isle of St. Marguerite, much like the earlier Virgin of the Forest, a 3-meter-tall sculpture carved in wood for an open-air event in Hajnówka in 1967.

In the so-called decade of Edward Gierek (1970s) authorities at various levels redirected artistic prowess toward developing public spaces. Sculptors received commissions for projects intended to decorate newly built housing estates and modernized urban arteries and roads throughout Poland. This period was an excellent opportunity to express themselves in significant and lasting forms, many of whom had not had such an opportunity before, as only monuments to political orders were realized in this area. Today, the open-air objects created at that time and preserved in cities such as Bialystok, Lublin, and Warsaw are exciting evidence of their cooperation with the authorities and their willingness to save the sculptural craft in a situation of growing conceptual tendencies. Teresa Brzóskiewicz realized three sculptures in Warsaw: Spring on Międzynarodowa Street and Two Rivers (Vistula and Volga) on Marszałkowska Street. The allegories of the rivers undoubtedly allude to Ludwig Kauffmann's sculptures of the Royal Baths (Łazienki) depicting the Vistula and the Bug, as well as to the Vistula chiseled by Tomasso Righi in front of the Old Orangery in the same place.

During this period, the artist also made small works in chamotte clay, which now occasionally appear at auctions.

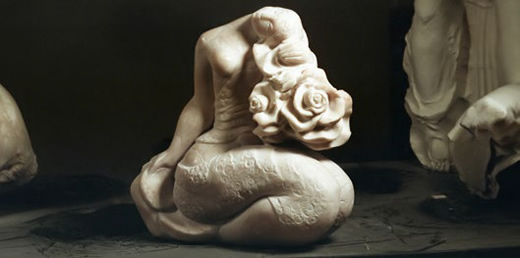

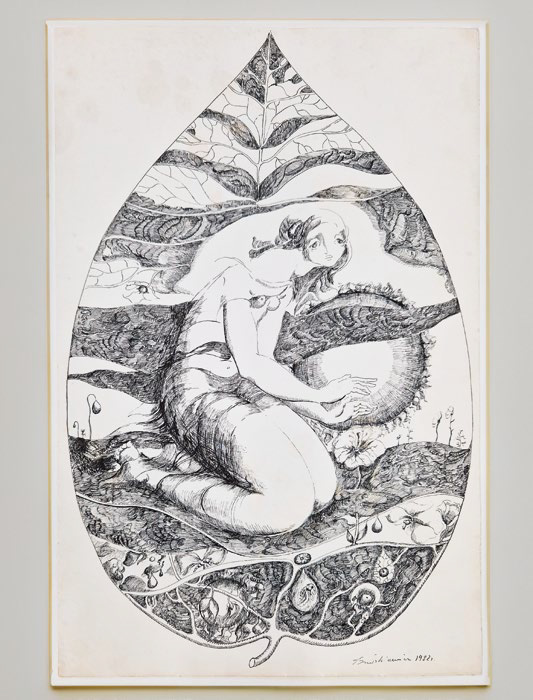

In the early 1980s, for personal reasons, Brzóskiewicz moved to the United States and settled in Union Grove, near Milwaukee (Wisconsin). She organized her artistic studio there, where she worked intensively. Constraints of a technological nature—the question of access to materials and workshop support—forced her to abandon work in metal in favor of plaster, ceramics, and, for the first time in her career, alabaster. She made some 20 works from the Rose and Woman series in this material, some of which are presented in the current exhibition. A significant event from her stay in the US was a performance by the excellent French mime, Marcel Marceau. Impressions from this performance resulted in a series of works with the collective title of Mime. In addition to sculpture, she also devoted herself to ink drawing—several works realized at the time in this genre are presented in the exhibition.

Teresa Brzóskiewicz with one of her drawings (1970s - Ina Stefanowicz-Schmidt archive)

Woman 1, ink drawing (1982)

(photo by Dorota Dzik-Kruszelnicka)

In the 1980s, Milwaukee was a small art center on an American scale with a relatively limited local interest in art. Nevertheless, Brzóskiewicz's work did not go unnoticed, and several articles in the local press were devoted to her, including a more extended interview; she also exhibited her work in local galleries, including the Cudahy Gallery of Wisconsin Art (Milwaukee Art Museum). She also had a solo exhibition at the Katie Gingrass Gallery in Milwaukee (1987), and a number of her works remain in private collections in the US.

She returned to Poland after almost ten years, where she found it difficult to find her way in the changed political conditions that completely transformed art. From this late period, in addition to female nudes carved in alabaster, there are mainly sculptures and portrait reliefs, including the head of Ignacy Domeyko for the Universidad de Chile in Santiago de Chile and the portrait of Professor Andrzej Wiercinski standing in the Faculty of Archaeology at the University of Warsaw.

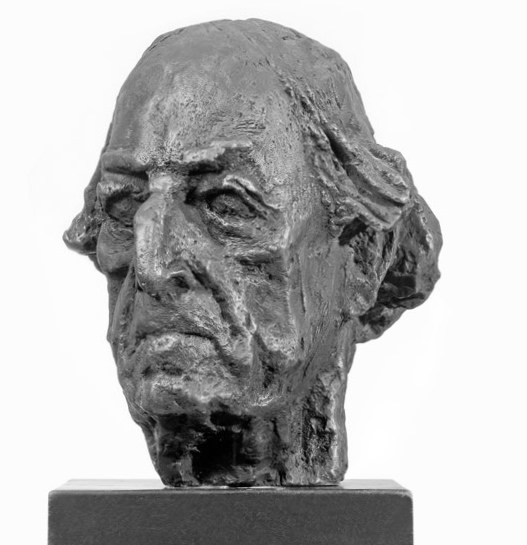

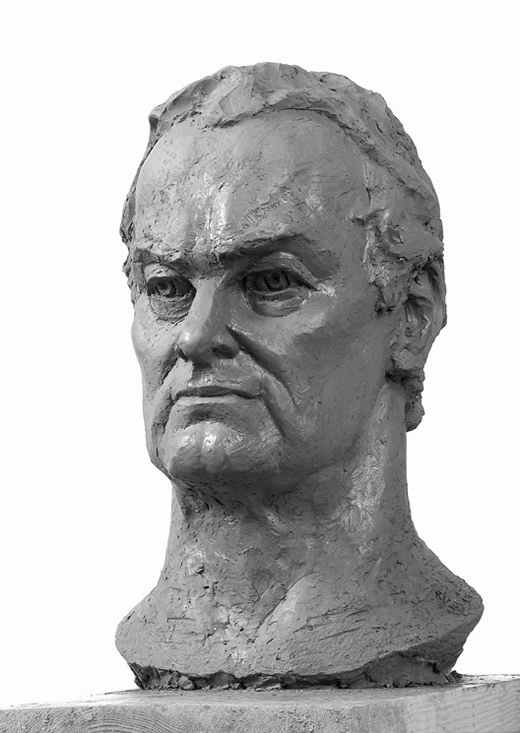

Portrait of Professor Andrzej Wierciński (2005)

bronze version at the Faculty of Archeology

of the University of Warsaw

(photo by Erazm Ciołek)

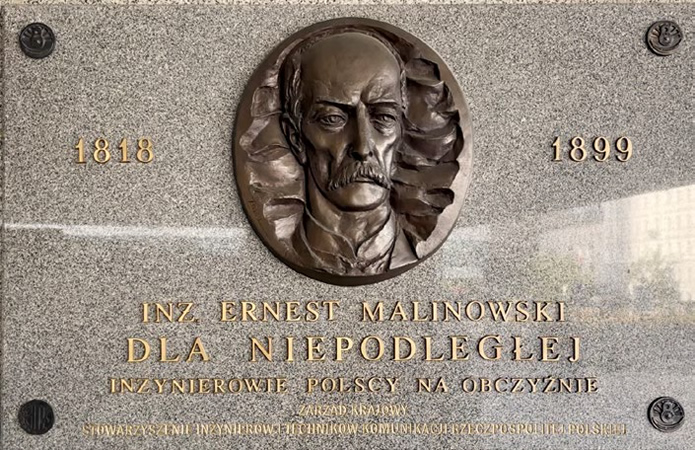

Portrait of Ernest Malinowski (2020 - copy of the original from 1996)

Emilii Plater Street, Central Railway Station, Warsaw

(photo by Marcin Jamkowski)

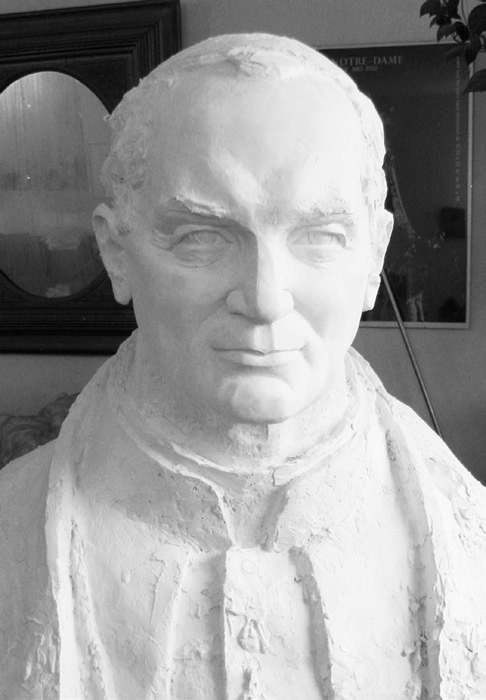

Portrait of Karol Wojtyła – Saint John Paul II (circa 2008)

She also created a bas-relief portrait of Ernest Malinowski, four casts of which adorn plaques commemorating his engineering and military achievements located at the Peruvian Army Museum (Museo del Real Felipe) in Callao (Peru), in a plaza in the Yanahuara district of Arequipa (Peru), in front of the Polish Engineers monument in Lima (Peru), and at the entrance to the Central Railway Station in Warsaw. Another bas-relief portrait by her of the prominent Peruvian historian Edmundo Guillén Guillén is in the Museo Inca in Cusco (Peru). She also made a bust of John Paul II; unfortunately, a casting of this sculpture, which captures the character of the Pope's figure well, was never made. She has also had, more modestly than previous ones, solo exhibitions in Paris (1990) and Lima and Trujillo (Peru, 1996).

Wisła (mid-1970s)

currently at ul. Gagarina 25, Radom

The hope is that the exhibition showcasing the work of Teresa Brzóskiewicz will be a stimulus for further research into her work. The artist deserves to be placed in the history of Polish sculpture in the second half of the 20th century and the early years of the 21st. During her lifetime, she was appreciated by the circle of artists today considered avant-garde, as evidenced by her participation in the Biennale of Sculpture in Metal and the project of a road connecting the MNW and Zegrzynski Reservoir. She has proven herself as an author of outdoor sculptures still present in the space of the capital, but also in Radom, where another half-lying female figure stands among blocks of flats from the communist era. At the Orońsko Sculpture Center, you can see her Dream from 1979, which foreshadows her later depictions of women's bodies rendered distinctly sensually in the small alabaster sculptures she worked on until the end of her life.

Joanna M. Sosnowska

(translated into English by Alexei Vranich)